Artist Draws From Childhood, and Uncovers a Model for Care

- Adam Smith

- Jun 18

- 5 min read

Updated: Aug 6

As artist Maggie Wong talks about her early childhood in Oakland, California, in the late 1980s and early 1990s, she pauses. Stopping halfway through a sentence describing the group to which her parents belonged during her youth, she considers how her words might be interpreted.

At first, she plainly refers to the organization, the League of Revolutionary Struggle, as “a revolutionary communist organization.”

Then she backtracks: “You could also call it a grassroots activist organization.”

This happens while Wong is explaining how her current artistic endeavor — a sculptural and newsprint project that focuses on the history of the League — profoundly shaped her early childhood.

“It’s been really interesting to work on this project in the past, like, six months, and to think, ‘What are the words to code it? What sets off alarm bells?’”

The word “communist,” she said, could invite the ire of some conservative groups who hear the word as a threat. And, the fact is, the group had strong influences from the revolutionary Chinese leader, Mao Zedong.

But her childhood, as Wong explains it in person and through her art, greatly benefited from her experience under a sort of version of communism that was more literal than political: communal childcare.

She grew up, as she puts it, as a “red diaper baby.”

Her parents and their colleagues were so busy working on their political activism in the League, which included the production of their multi-lingual newspaper, Unity/La Unidad, that by the time they started having children, they were posed with a problem: How would they keep up their activism while also raising their kids?

“They were pretty young when they started,” says Wong. “And then people started getting older and having kids. And they were like, ‘How do we support our comrades and their families in this movement?’”

So, the members of the League of Revolutionary Struggle – including Wong’s parents – began “methodically” hammering out every logistical detail of how their children would be cared for –who would take care of the babies and who would take care of the older kids, who would pay dues and how caretakers would be compensated.

“They wanted it to be enriching for their kids.”

Her father, Eddie Wong, a Chinese American born in the U.S. to immigrant parents, and her late birth mother, Anna Whittington, who hailed from the Mississippi Delta, were highly active in the League. Her father contributed to Unity/La Unidad over several years, writing articles and reviews and taking photos.

“It really freed up time for women, especially, to engage in political leadership,” said Eddie Wong, now in his mid-70s, during a phone interview with the Sampan. He said he and other activists all had day jobs on top of their work with the League. Some were factory workers, some were educators, and others were community organizers. “It was a really busy schedule,” he said, joking about how all the kids thought it was normal to be dragged around to protests and demonstrations.

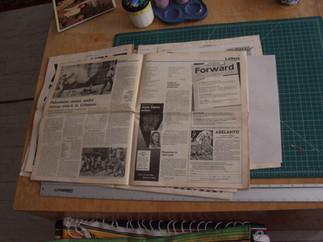

Today, throughout Maggie Wong’s studio in the Boston Center for the Arts’ South End building are artifacts of her parents’ lives. Copies of the newspaper, Unity/La Unidad, are pinned on the wall and spread out on desks and tables.

One headline from the 1980s reads, “Palestinian camps under furious attack in Lebanon.” Another story details a report from the 1985 United Nations forum for women.

Copies of a Marxist-Leninist booklet, “Forward,” are also displayed on her work table, one featuring a story about the “Struggle for Chicano Liberation.”

The room, in many ways, feels like an extension of her art project. Each booklet, each news page, seems to be set deliberately in its place.

Her own newspaper, which is part of her art project, is also on display. The work is part art, part zine-style newspaper and part historical documentation, containing bits from the original publication and mixed with interviews of others who were in the childcare program.

“I’m remaking the paper in some way,” she explained of her art project that began in 2023, pointing to pages posted on her wall during a recent weekday.

Artist Maggie Wong's studio in the South End in Boston; Photo by Adam Smith.

In addition, she has pieces of her sculptural works stored throughout the room, including letterpress furniture that is now fashioned as children’s blocks, some painted bright colors. Others are components of a papier-mâché sculpture resembling a drafting desk for laying out the paper that underneath has an area “reminiscent of a fort for kids to play in.”

Wong was born in 1988, just a couple years before the League of Revolutionary Struggle’s Unity/La Unidad newspaper, which ran from 1978 to 1990, was disbanded. Several parents continued the childcare system for a few years after, she said, before that component ended as well.

It wasn’t perfect, said Wong, as she recalled some kids resented they couldn’t be with their parents more, but others, she said, appreciated that “their parents were doing something big.”

“We grew up in a system in which we felt really supported as kids,” she said. But her parents never explained that she was growing up in a “communist” parenting community.

“They were very secretive,” she said. “We were never told, ‘These are communist values that we have.’”

Today, her artistic interpretation of the communal childcare program feels especially relevant as working parents meet the impossible costs of care, which can run thousands of dollars a month, and the inability to make ends meet on the income of one parent alone.

“When it dissolved, people were like, ‘This did so much for our families,” says Wong, of the communal childcare system.

“We’re all kind of thinking, is it possible to do this now?”

Her father agrees it would be a challenge, saying a close network of friends is key. He also sees parallels to what is happening politically and economically now in the U.S. to what was happening through the late 1970s to 1990s.

“Things have gotten much worse,” Eddie Wong said. “The things we were fighting for, fair wages, civil rights, political representation. All those things still apply.”

When asked why she pursued art, Wong said she essentially “didn’t have a choice,” because she was so heavily influenced by her parents, especially her father who was a filmmaker and photo editor and writer. Wong earned her Master’s in Fine Arts from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and before coming to Boston was an educator-in-residence at the Luminary in St. Louis, and a lecturer at the institute. She’s exhibited her work in the Mana Contemporary Chicago, Comfort Station, Annas Projects, the Chinese American Museum of Chicago, where she debuted this project, and elsewhere. In addition to pursuing art, Wong is working part time at Brandeis in the Fine Arts department, teaching studio classes. She is also the Gallery Coordinator at the Wagner Foundation.

Her current project comes after several other modern sculpture exhibits using wood and metal and wall-sized graphite drawings.

But her Unity project appears more than art – combining history, commentary on a human necessity (childcare) and, for Wong, family.

Working with her father on the project, she said, “we’ve never been closer.”

Eddie Wong said he admires his daughter for taking on the project.

“I was gratified to see her reaching out to her peers,” he said and for “making sense of her childhood.”

“Maggie and her peers realized they weren’t like other kids. They have parents who were full-time activists. They were raised by a village in a sense.”

Wong will present at a workshop on Aug. 23 at The Boston Public Art Triennial.

Comments