For Phillip Eng, Public Service Suits Him to a ‘T’

- Adam Smith

- Jul 25, 2025

- 12 min read

Updated: Dec 30, 2025

MBTA boss sits down with Sampan to talk about the past, present and future of Hub’s beleaguered transit system

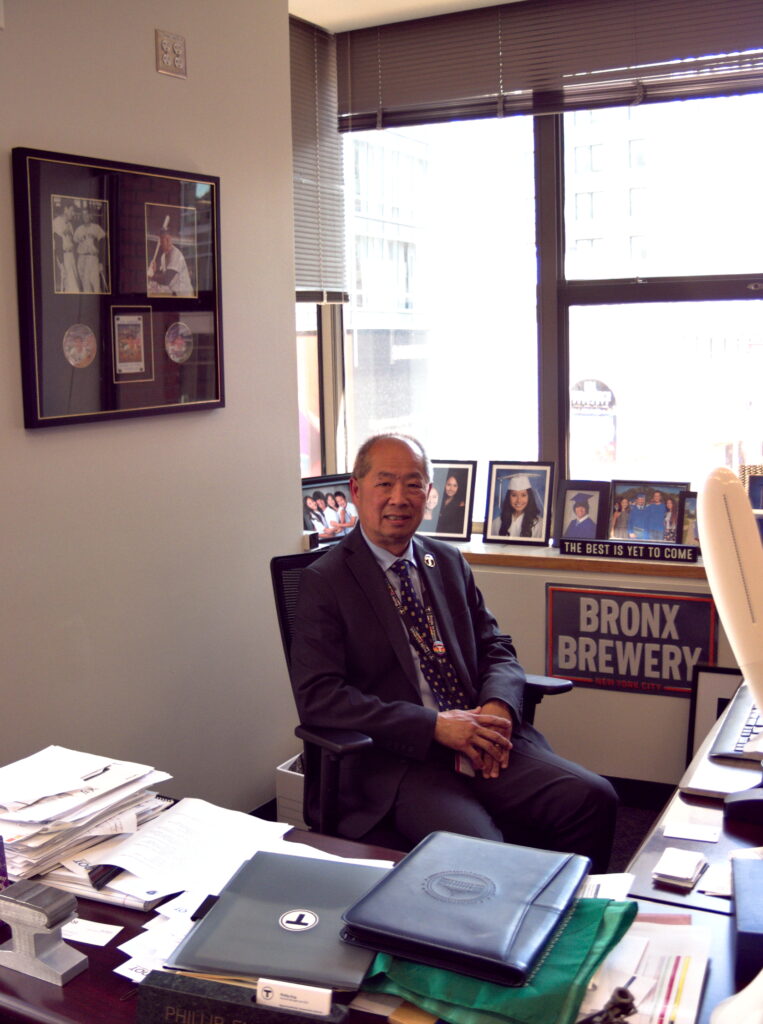

Everyone has their own image of the T. For some, it’s that cartoonish CharlieCard guy and for old-timers, it’s still the long-gone 85-cent token. For others, it might be their local bus number or subway color. But for many these days, it seems to be the friendly face of the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority’s general manager, Phil Eng.

Indeed, the New York native has become as much a local celebrity as the honcho of the unwieldy public transportation system that is the MBTA. His name appears all the time on social media sites like Reddit, in Bostonian’s blogs, in the news, and his image even appears in selfies online (think about that for a moment: Have you ever seen an MBTA boss in so many selfies with riders?).

So when the opportunity came to sit down with Eng in his office, this reporter was actually … not looking forward to it.

What do you ask a guy who’s so often in the press? A guy whom every Bostonian already knows about? A guy whom the Boston Globe just profiled in a lengthy feature that went so far as to interview his 93-year-old mom in New York?

Phillip Eng seems to know all the little details about the buses and the trolleys, about the tracks and the station access for people with disabilities. At the same time, he seems to be a big-picture guy, with eyes on what new tracks are needed and how they should be built. And on top of all of that, Eng is sold as the rare engineer who’s also a charismatic leader that could win needed funding for repairs and to persuade reluctant politicians. In sum, Eng appears as the capable and friendly face of the T – so friendly that perpetually disgruntled Bostonians are able to overlook immediate problems of their trips to work and home because of their faith in Phil.

Is it all really possible?

After all, we still see the headlines about problems with the T. Trains down here. Bus breakdowns there. The track inspection scandal. Delays. Just weeks before Sampan sat down with Eng in his office – which is near the Boylston Street T stop that opened in 1897 – this reporter would still get on a Green Line trolley with a broken cash machine, allowing entrance without pay. And weeks after the interview, hundreds of people had to be evacuated from a Blue line tunnel.

Eng’s Track to Success

From everything you can read about him, Phillip Eng started out with a story familiar to the Chinese American experience of his generation: a child of immigrant parents laboring long hours in a laundry shop – parents who were so concerned about their kids fitting in that they changed the English spelling of their family name, according to a Boston Globe story. Eng, who told the Sampan he enjoyed playing with trains and matchbox cars as a child, would over several decades steadily rise up the ranks of public transit systems – from a junior engineer at the New York State Department of Transportation to the top of New York’s Long Island Rail Road, and now to the top of the MBTA. His hard work and likable personality would pay off. Yet in his career progress, he was also, unwittingly or not, laying a track of opportunities – a track that with the help of his contemporaries – was leading to an era very different from his parents’. Now, in his 60s, Eng has ended up in a new generation, a time when Michelle Wu is mayor of Boston. A time when some of the top U.S. companies are run by people like Lisa Su (AMD) and Jensen Huang (Nvidia) and when people follow investing gurus like Tom Lee and see John Yang leading the nightly news.

An Old System in High-Tech World

Eng seems to be constantly looking ahead to what’s possible and does not make excuses for what’s not working right. He addresses the T’s many woes as problems that needed to be solved with a combination of clever creativity, engineering and, importantly, more funding ( as he said at his first press conference to the state’s riders, “Sometimes you have to spend a little money to save a little money.”).

“Whether it's two years or 20 years, you're never done learning all the different things that you can do better as an agency. I’ve been in transportation for over 40 years, and we have to evolve with the communities we serve. We have to evolve with businesses and development and make sure that we are always keeping an eye out for those patterns, because what we don't want to be is reactive,” he told the Sampan.

Eng is big on the idea of ending the cycle of always fixing leaks and putting out fires (figuratively, and literally) and, instead, focusing on making the system better. But it’s a tall order.

The T is among the nation’s Top 5 busiest public transit systems, depending on how you measure it, and much of the rail and bus lines crisscross through the very old and very dense Downtown area of Boston – a city where people typically want things improved, but don’t want to put up with the digging, demolitions, costs and construction interruptions needed to get there. Last year, the MBTA, had a total ridership of 245,498,400 -- including on the subway, light rail lines, the Silver Line bus and other bus services, a dozen commuter rail lines, and ferries. Eng himself, even coming from New York, will easily acknowledge that it would be so much easier logistically to make upgrades if the tracks and stations were out in the boonies.

But they are not. What was perhaps most surprising during the interview was what Eng said when posed with the question of: Could the T ever become modern? Whenever people talk about the subway’s problems, the excuse is so often its age – that its history can be traced back to the late 1800s.

Yet Tokyo’s subway system goes back pretty far in history, too, and it looks nothing like the T’s patchwork of a system. Many other cities around the world also have old systems that are more modern and reliable. Could the MBTA one day be like those?

“Absolutely,” says Eng.

Modernizing the T, he said, is achievable.

“I always say, the infrastructure, the engineering, that's all achievable. That's the easy component.”

But Eng is practical, as well, noting that the funding of all of the different components needed has to be balanced with other needs of society. (The MBTA board just reportedly passed its multi-billion dollar budget that would rely heavily on state funding in addition to earnings from riders and other sources to cover daily operations; the MBTA is set to get hundreds of millions of dollars from the state for fiscal 2026 to help cut the authority's deficit. Perhaps that’s why Eng constantly also praised T-funding advocate Gov. Maura Healey during this interview, too.)

“It's not just transportation needs, but there's so many needs that the state is facing,” he said. “I'll make my pitch for transportation, but at the same time, you know, there are so many other agencies that I know need to be funded properly as well, because all these different sectors come together.”

This is even more so amid a host of federal funding cuts amid the second Trump administration. Eng also pointed out how historic buildings and structures also need to be respected.

“When you take a system as old as ours, and, you know, I came with the same experience in New York City, there's a lot of historical characteristics of stations that you have to be mindful of when you're looking to upgrade, modernize, rebuild, or even just make accessible,” he said. “Having said that, I fully believe and expect that we will make our system 100% accessible.”

History of … Trouble

Eng appeared well aware, after more than two years on the job, that coming to Boston with a clean slate gives him an advantage.

“I think some of the things that I observed early on is that the agency has been struggling, obviously, and that in the public eye, it could do no right. And I think because of that, it was hard (for the previous administrations) to make some bold, tough decisions that I was able to make, because I did not come with that (baggage). I came here with a clean slate, and it gave me a little more freedom, I think, to make those decisions,” said Eng. “I also have to admit I wouldn't have come here if I didn't think Gov. Healey and Lieutenant Gov. Driscoll would not be as supportive of transportation as they said they were. … You know, without them being willing to go bold and go big, I couldn't do what I'm doing.”

It’s true. The MBTA, as painfully well documented and experienced firsthand by unhappy riders, had been having problems for years before he came on board. While many still blame Covid-19 for much of the T’s woes, months before the pandemic’s start, an MBTA report already put the price tag for fixing and replacing old equipment and infrastructure at an impossible $10 billion.

And of course the system is constantly plagued by bad press, including the recent federal charges against four former MBTA employees and one current one who allegedly falsified Red Line track inspection reports. The recent image of the Blue line evacuation doesn't help, either.

Underscoring the persistence of the view that – as Eng put it, the T “could do no right” – when asked at what point he felt like he really knew the system inside and out, Eng answered the question differently. Instead of acknowledging that any job has a learning curve and every system has its own quirks, he said:

“I think if you're asking me, when did I start to realize where we needed to shift the agency in terms of how to best prioritize things, then it really was about the latter part of 2023 when we started to make changes in the organization. That’s when we started to really change the way we went about getting work done.”

That was when, he said, he brought in new expertise like Sam Zhou, the MBTA's chief engineer, who was present at the interview.

“Sam has over 35 years of transportation experience, and as our chief engineer and head of capital delivery, is working alongside with the other leadership that we reorganized, including some that were here already; that's when we started to realize that there's a different way, a better way of doing things.”

But part of Eng’s job, he said, was selling the T itself, to riders, and potential riders, and to the workers who so often got a bad rap.

“How do we demonstrate to the workforce that the new way is better and that they can embrace it?” said Eng. “I think it was some of the early-on shutdowns where we pushed ourselves hard to get more done than previously people would believe. But when we actually had those early successes, I think we could start seeing that we were starting to turn the corner internally, and that helped us build up the momentum. That also helped us accelerate some of the thought process of, you know, that we could even be more aggressive going forward.”

Driven By ‘Public Service’

When asked when he realized his calling was in public transit, Eng corrects the questioner.

“I think my calling is public service,” he said. “Transportation happened to be the field that I landed in.”

He said enjoyed trains as a kid, and had a knack for math and science, which helped shape his career path.

“I think that naturally lends toward this area, you know, but maybe it's kind of interesting that I didn't define success as saying, 'I had to be president of New York City transit, or president of Long Island Railroad, or GM and CEO of the MBTA.' I really defined success in each role I had and just doing the most I could with what it was.”

Over his nearly 43 years in public transportation, Eng said, the real reward was solving tough problems and finding ways to “creatively do those repairs, just as we're trying to do here with track work, overnight weekends, keeping lanes open. You know, that's what we're doing here with our infrastructure. How do we repair tracks, replace ties, replace signals and keep the trains moving?”

But many must be wondering, is the hype surrounding Eng for real? After all, problems still lurk, it seems, daily, for one bus or train line or another.

Many people, however, have stepped up to endorse Eng.

"I think Phil Eng has been a breath of fresh air for the T," said Mike Martello, PhD., civil engineer and MIT-affiliated researcher, who's studied climate change's challenges to the MBTA and other transit systems. "Hiring someone with his credentials and competencies from an outside peer agency was a smart move, as he's proven to be untethered to some of the T's institutional inertia."

The Sampan reached out to Martello solely based on his expertise and past study at MIT. Yet he had only praise for Eng.

"Overall, I think he's doing a great job. It's hard to say what the future will bring, though I think funding is always a pervasive challenge for the MBTA. Depending on how federal funding shakes out over the next few years, the MBTA budget may end up in a serious pinch and would be a serious challenge to navigate."

But what about the typical T worker?

Just before the Sampan interviewed Eng, this reporter by chance met a Silver Line bus technician, Ray Crowder, who said he had been working for 23 years at the MBTA. He couldn’t stop talking about how happy he is on the job now that Eng came onto the T.

The technician, who is also member of the Local Machinist Union 264, had only praise for Eng; praise that almost sounded like relief.

“He actually cares,” he said, in a follow-up phone call, asking about his impressions of Eng. “He is taking our words into consideration. He’s been really good about getting us the budget that we need.”

Then, he said, “The MBTA is not the political dumping ground it was years ago…. I’ve very optimistic about its future.”

_____________________________

SIDEBAR:

Mike Martello, PhD., is a civil engineer and MIT-affiliated researcher, who's studied climate change's challenges to the MBTA and other transit systems. We spoke to Martello about the Massachusetts Bay Transportation System's Phillip Eng and the challenges facing the T.

Sampan: I can't remember a general manager of the T who seemed so popular as Eng. What are your general thoughts about his performance over the past couple of years and the obstacles in front of him?

Martello: I think Phil Eng has been a breath of fresh air for the T. Hiring someone with his credentials and competencies from an outside peer agency was a smart move, as he's proven to be untethered to some of the T's institutional inertia. Overall, I think he's doing a great job. It's hard to say what the future will bring, though I think funding is always a pervasive challenge for the MBTA. Depending on how federal funding shakes out over the next few years, the MBTA budget may end up in a serious pinch and would be a serious challenge to navigate.

Sampan: When I interviewed him, he seemed to believe the T could really become a first-class system one day, modern and not the patchwork that is seems like today…. Given the challenges that Greater Boston faces -- geological, geographical, political and historical -- do you see this as a real possibility?

Martello: Anything is possible with enough political and financial capital. That said, I think truly modernizing the T would require some unpopular decisions that would likely end up leaving behind winners and losers. On top of a blank check, I think serious changes to the system will require real political support and serious public engagement that may never fully materialize. I also think it depends on what you consider to be world class. In a lot of ways, the MBTA is already there, though if you're thinking of a system designed with tomorrow's mobility needs and travel patterns in mind, there's a lot of work left to be done.

Sampan: Since this just happened, what, if anything, can we take away from the Blue line evacuation? On the one hand, it seems like a glaring example of the problems that have been plaguing the T for years, but on the other hand, everyone was apparently safely evacuated, which seems like an amazing feat. Is this both a sign of the problems we have and the responsiveness of our T and emergency systems? Or something else?

Martello: Unfortunately, with a system as old as the T, these type of events are inevitable. From what I've read, the emergency response was a great example of the T operating well under pressure. Hard to say if this will be a harbinger of similar problems in future, though I personally would not bet on that being the case.

Sampan: One thing that comes up time and again is how old our system is and how that's why it's the way it is. But I think many other systems are old, such as Tokyo's metro system, but they don't look like ours, and function much better. Do you have any thoughts about that excuse?

Martello: Age is likely a limiting factor, though I think funding is still the greatest hurdle. Transit systems are quite expensive to modernize, especially in the US, relative to peer agencies abroad. There are some aspects of the MBTA system, such as the geometry of the tunnels, thinking of sharp turns on the Green Line, like at Boylston for instance, that will inherently impinge upon any modernization efforts. In that sense, the age of the T is a bit of a unique obstacle, insofar as many of the existing tunnels were designed for service standards of a different era.

Sampan: Finally, climate change. How big of an impact will be climate change, do you think, on the T in the coming years? Not only on the subway lines that run through downtown and their structural integrity, but on the demand for power, and the rising sea levels?

Martello: … I'm cautiously optimistic that the impact of climate change on the T will be minimal, given their focus on the issue and organizational capabilities. That said, funding for climate resilience measures over the coming years will be key to minimizing the impact of climate change. Sea level rise, particularly in the latter half of this century, may yet well pose an existential issue for some of the coastal communities the MBTA serves, thinking specifically of the portions of Revere serviced by the Blue Line for instance, though that's still a pretty distant issue, at least for the moment.